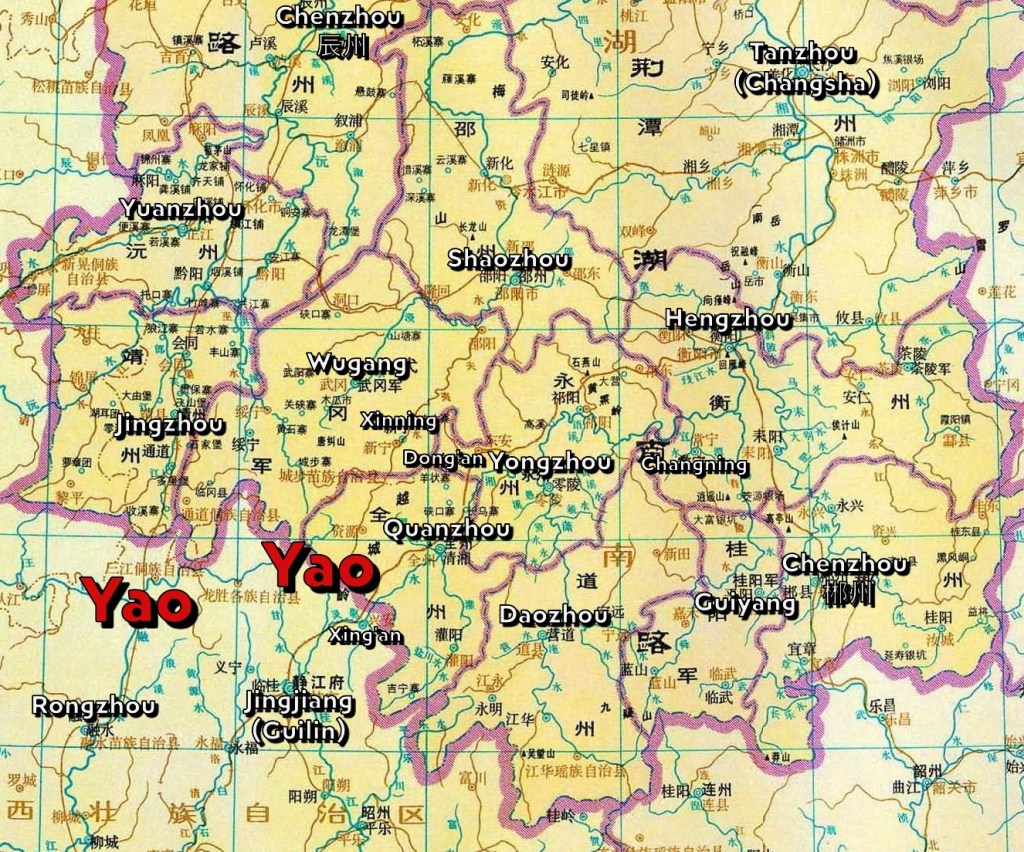

The cases of the “Cooked Li” in Hainan and the Yao in the Guilin area (see source 5.11) show that the Song state’s challenges on the southern frontier were not limited to deterring or repelling indigenous raids and securing the allegiance of indigenous leaders. The state also often had to devise measures for preventing Chinese “frontier commoners” from interacting with the indigenous peoples in ways that it considered detrimental to stability, which might include conflict, collusion, or commercial transactions involving the transfer of land. This became increasingly difficult as the number of Chinese settlers in these areas continued to grow, as the indigenous settlements gained a reputation as places where criminals could find refuge from the imperial state, and as increasing numbers of indigenous communities began to render forms of service and taxation to the state in exchange for local autonomy, official titles and rewards, and legal trade with the Chinese settlers (a relationship that was commonly termed as “bridling” or as transitioning from “raw” to “cooked”).

The four passages translated below serve as examples of this complex dynamic on the Hunan frontier, as seen from memorials submitted to the Song imperial court in 1168-1214. All four are from the Song huiyao jigao (Draft Reconstruction of the Song State Compendium), a reconstruction of the lost Song huiyao (Song State Compendium) based on the many fragments preserved in the Yongle Encyclopedia of 1408 (much of which was itself lost during the nineteenth century). The “barbarians” on the Hunan frontier were known to the Chinese as Yao, and were descended from the ancient “Man of the Five Rivers” and the Chinese people who had joined them over the centuries. However, they were probably linguistically and culturally diverse, consisting of groups that are now officially classified as Yao, Dong, and Miao. The modern ethnonym Dong 侗 is derived from dong 洞/峒, the standard term for a settlement or community of southern indigenous peoples in the Song.

~~~~~

From the section “Foreign Barbarians (Fan-Yi), Part 5”

On the eighteenth day [of the second month of the fourth year of the Qiandao era (March 29, 1168), an official reported: “The Man in the three prefectures of Chenzhou, Yuanzhou, and Jingzhou1 are generally dispersed in various settlements (dong 洞) and not under any unitary leadership. They did not originally have any desire to rebel, but clerks in the frontier prefectures and counties who had been found guilty of offenses, as well as other scoundrels, fled into the settlements and used various means to incite and entice them. As a result, they began raiding the lands under state jurisdiction (shengdi 省地). We request that the relevant authorities consult and compare the regulations pertaining to this. Anyone who captures or reports a person plotting to enter the mountain valley settlements (xidong 溪洞) is to be rewarded, and anyone who fails to take precautions and thus allows such people to escape across the frontier is to be punished; the rewards and punishments should be raised above the usual level.” An edict was issued ordering the local authorities to study the situation in detail and establish the necessary laws.

On the eighth day of the fifth month of the eighth year [of the Qiandao era] (June 1, 1172), an edict was issued: “People of the settlements under the jurisdiction of Changning county in Hengzhou prefecture (Changning, Hunan) are not to buy and own property in the lands under state jurisdiction; in turn, local imperial subjects are not to sell farmland to the settlements in exchange for land in the mountains and forests. Any violation, no matter how slight, will be investigated and punished. Prefects and magistrates who fail to enforce this law will be penalized by being reduced to commoner status. If people of the settlements are willing to sell the property that they have acquired [in the lands under state jurisdiction] to people of the prefecture, they will be allowed to do so. The governor of the province is ordered to oversee this process and report to the court.”

An official had reported: “The people of the settlements often buy farmland outside the settlements, in the lands under state jurisdiction, for their own use, and hire people of the lands under state jurisdiction to farm for them. Every year, they use [the produce] to pay taxes to the state. The officials worry that they will make trouble, and are relieved that they pay taxes to us, so they have allowed this practice to continue without asking questions. As a result, much of the farmland [in the county] is owned by the settlements, and many of the people work for the settlements.” The edict was issued in response to this.

[Translator’s note: The text does not explain why the imperial court objected to Chinese subjects selling farmland to and working for the Yao people of the settlements. The most likely reason is that the wealth and manpower thus gained could make it easier for the Yao to rebel and raid the county. A secondary reason might be a loss of revenue to the state, since the Yao typically paid lower taxes in rice than Chinese peasants.]

On the fifth day of the fourth month of the tenth year [of the Qiandao era2] (May 7, 1174), an edict was issued ordering the military commissioners of Hunan and Guangxi to close off, where possible, all newer footpaths leading into the settlements. All measures for redeploying troops to patrol these paths, or to impose restrictions and tolls, were to be discussed and coordinated carefully. This was because Quanzhou prefecture (Quanzhou county, Guangxi) had submitted a memorial saying: “This prefecture is highly connected to the settlements, and its people were originally not treacherous or cunning. It is only because they lived in peace and neglected to take precautions that fugitives from every corner have converged here and made it their lair. They come in and out of hiding together, gradually leading to disorder and chaos. Take, for example, the commoner Yang Zaixing of Wugang (Wugang, Hunan) in previous years, and Chen Dong of Guiyang (Guiyang county, Hunan) in recent years; both of their rebellions began like this.3

It is not that the imperial court’s laws are insufficiently strict; nor is it that the governors and prefects have failed to follow them. The reason why they cannot prevent such incidents is that traveling merchants often take side paths in order to avoid tolls; meanwhile, lawless vagrants who commit crimes, knowing that they cannot escape the law, often use these footpaths to flee into the settlements; so do bandits whose death sentences have been commuted to exile to Guangnan (Guangdong and Guangxi), some of whom escape en route, others of whom arrive at their place of exile but then form gangs to escape.

Even though the laws prohibiting this are comprehensive, the frontier stretches over a long distance and has many hidden streams and small paths. There is a path that starts from Datongxu in Xing’an county of Jingjiang prefecture (Guilin); this connects to Yang Zaixing’s former settlement, and was the very route that he once used for going out to raid. There is a path that starts from Shixian in Shaozhou prefecture (Shaoyang, Hunan) and runs past Pengxi Settlement in Xinning county of Wugang garrison. There is a path that starts from Dong’an county in Yongzhou (Yongzhou, Hunan), and one that starts from Eighty li Mountain Pass in Wugang garrison. One can get to the settlements by any of these paths. Since they cross over the territory of neighboring prefectures, I, your subject, cannot impose restrictions that apply to areas outside the jurisdiction of my prefecture. I request that measures be taken to close off the paths by deploying troops from the nearby patrol stations to garrison their entry points. Patrolmen who are currently idle should be moved and stationed at these entry points to focus on guarding them.” The court accepted this request.

On the sixteenth day of the third month of the seventh year [of the Jiading era] (April 27, 1214), an official reported: “I humbly observe that in the three prefectures of Chenzhou, Yuanzhou, and Jingzhou, the prefectural subjects (shengmin 省民) live in the center4, while in the periphery are the Cooked Households (shuhu 熟戶), the Mountain Yao (shanyao 山徭), and those known as Settlement Men (dongding 峒丁), who live close to the raw zone (shengjie 生界).5 Winding along the frontier and extending deep into it are very many regiments and settlements (tuandong 團峒). The prefectural subjects can live in peace most of the time due to the protective shield provided by the Cooked Households, Mountain Yao, and Settlement Men combined. When the commanderies (prefectures) were first established, the various zones were allocated in great detail, and the defensive preparations were comprehensive. Hence there were specialized laws and protocols for the settlements, solely for the purpose of maintaining peace on the frontier. As soon as the alarm was raised that the raw zone [Yao] were raiding the lands under state jurisdiction, the regiments of the Cooked Households, the Mountain Yao, and the Settlement Men would take up their spears and arrows to fend them off. Without any cost in grain and soldiers to the prefectures and counties, these regiments would happily serve us at great risk to their lives. This is presumably because our dynasty had an effective system for motivating them, which was as follows:

The Cooked Households, the Mountain Yao, and the Settlement Men owned farmland but were not allowed to sell it without authorization. Regardless of the size of their land or the breadth of the mountain forests they had cleared for cultivation, each man’s plot was clearly demarcated and he was allowed to cultivate it freely. Every able-bodied male was registered and levied a tax of three pecks of rice, but was not subject to any other taxes. The Cooked Households, the Mountain Yao, and the Settlement Men were happy to have land to farm, so when raids came from the raw zone, they fought with all their might to defend us so as to protect their own fields and property.

But in recent years, the Yao and Lao of the raw zone have raided the lands under state jurisdiction, and the prefectures and counties have had no means to prevent this. This is all because they could not follow the good model of the past. In the special regulations for the settlements, the Cooked Households, the Mountain Yao, and the Settlement Men were not allowed to sell farmland to prefectural subjects. This was presumably due to concern that they would become impoverished and lose their sense of commitment to serving us. Now, the prefectures have carelessly allowed the Cooked Households, the Mountain Yao, and the Settlement Men to sell their fields to prefectural subjects, so that they could profit from the tax on commercial transactions, and also because prefectural subjects who bought more farmland would pay taxes above the quota they were registered for, thus increasing revenue for the prefecture. Meanwhile, the Cooked Households, the Mountain Yao, and the Settlement Men continue to owe their tax in rice, and in the face of harsh demands for them to pay up, most of them can no longer make ends meet. They eventually flee into the settlements of the raw zone, where they receive employment in order to feed themselves, some as guides [for raiders], and some as business partners. They incite the raw zone to raid the lands under state jurisdiction, leading to endless chaos and harm. I, your subject, have only directly observed this in three prefectures, but it is likely to be happening in all the parts of Hu-Guang6 that border on the Man. I request that a clear edict be issued to the governors of Hu-Guang, to be passed down to the prefectures, ordering that in all areas with settlements, the Mountain Yao and Settlement Men are not to sell their property to prefectural subjects without authorization. Any violators will be punished as breaking imperial law. Let their [previously sold] farmland be returned to them, and before long, the Mountain Yao and Settlement Men will all have their own land to cultivate and be content with their livelihood, rather than recklessly causing conflict on the frontier. This is truly the best strategy for pacifying frontier peoples.” The court accepted this request.

- These prefectures correspond roughly to the jurisdiction of Huaihua city in modern western Hunan. ↩︎

- This should actually be the first year of the Chunxi era, as the era name was changed in 1174. ↩︎

- Yang Zaixing was a Yao leader who led a rebellion against the Song state in the late 1120s and early 1130s; he was probably not the same person as the Southern Song general Yang Zaixing (d. 1140), who was his contemporary. Chen Dong led a major revolt in southern Hunan in the 1170s, capturing Daozhou (Dao county, Hunan) and Guiyang; the rebels are said to have included both Chinese and Yao who were angered by over-taxation. The Song state mobilized thousands of troops to defeat and capture him in 1179. ↩︎

- Reading 十 as a mistranscription of 中. ↩︎

- The prefectural subjects were Chinese civilians, while the Cooked Households, Mountain Yao, and Settlement Men were different categories of Yao who owed some form of obligation to the Song state in the form of taxes or military service. The Yao in the raw zone, on the other hand, were fully independent of Song state authority. ↩︎

- Hubei, Hunan, Guangdong, and Guangxi ↩︎