The passage below is excerpted from an essay by Su Shi’s youngest son Su Guo (1072-1123), who accompanied him during his Hainan exile (see source 5.9). It was apparently composed in Hainan itself. Su Guo’s prose style was so similar to his father’s that he was nicknamed “Little Dongpo,” Dongpo (Eastern Slope) being Su Shi’s nickname. However, it is quite possible that this essay was actually written by Su Shi but published under Su Guo’s name, since it would have been dangerous for Su Shi to wade into policy debates when he had already gotten into trouble before for his outspoken criticism of Wang Anshi’s New Policies reforms.

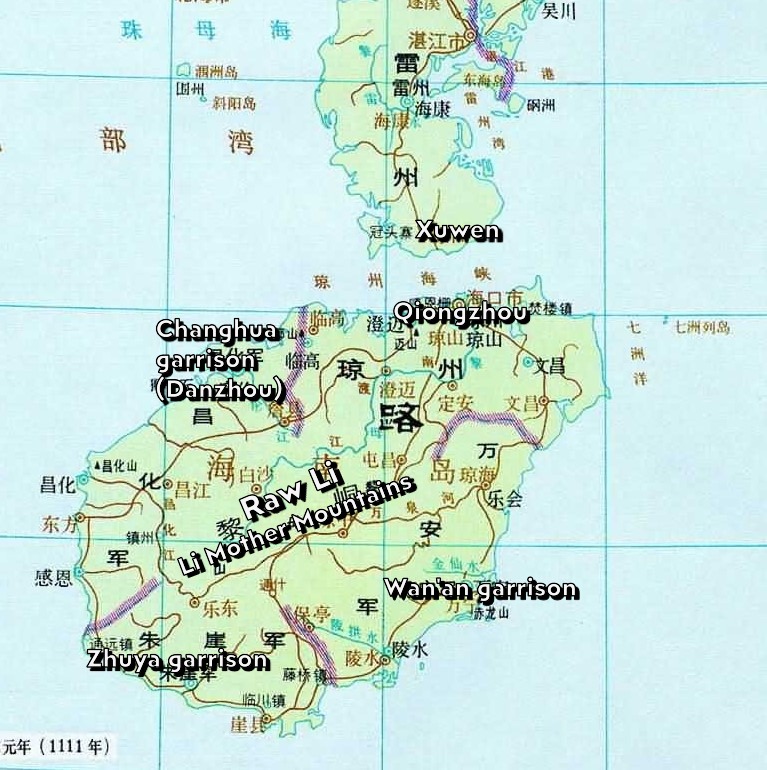

The essay engages with ongoing debates over the correct policy for managing the restive indigenous population of Hainan, known to the Chinese as the Li 黎 or, in Cantonese, Lai (a transcription of their endonym Hlai). The author argues against the options of military conquest, cultural assimilation, and economic blockade, deeming each to be impractical based on what he has learned from talking to the local populace. He then proposes his own favored solutions. It is interesting that he opposes assimilating the Li as taxpaying imperial subjects by employing the dehumanizing rhetoric about “barbarians” typical of Chinese anti-expansionist discourse going back to Jia Juanzhi (see source 2.4), but then shows the ability to empathize with the Li people’s legitimate grievances against deceitful Chinese settlers and corrupt local officials and clerks. He is even able to recognize that Chinese settlers are tempted to join the Li to escape their heavy tax burdens, though he evidently cannot resist aiming another jab at the New Policies in the process.

~~~~~

I humbly observe that the matter of the Li people of Hainan has been intensely debated, with no consensus reached on the costs and benefits. Although this is like a mere case of scabies for the imperial court1, not worth any discussion, nonetheless a noble man feels shame if even one commoner does not obtain the means of livelihood. Previously, some have proposed destroying their nests and dens and leveling their land. Others have proposed conscripting their people and changing their customs. Yet others have proposed cutting off trade with them to exhaust their strength. But none of these proposals have gotten to the heart of the matter. As a result, we live in terror and alarm, our officials are killed and our commoners captured, while those in authority have grown used to seeing this and dare not do anything about it. Those above and those below cover up the truth, so that the dead have no redress and the living have no protection. The situation is extremely lamentable. Is this not because those discussing the matter do not understand the roots of the costs and benefits, while no one has reported the truth to them?

I am in Hainan caring for my father, and am in fact classed as a commoner. Those with whom I interact are old farmers and common townspeople. I don’t have the power to either help or harm them, and those who speak with me forget their usual reservations [when speaking with officials], thus I have gained exceptionally detailed knowledge of their point of view. If I remain silent, who would speak for them to those in authority?

Some have argued: “The Li people’s settlements do not have multiple layers of guarded gates and night patrols, nor do they have armor, shields, swords, and polearms for self-defense. They merely gather and disperse among the mountains, forests, streams, and valleys like birds and beasts. If we use a strong army to catch them by surprise and burn their villages, we can eliminate them in one stroke.” Those in authority believe this to be true. Why? Because if one looks at a map, the Li have only a small amount of territory that it should not take more than several thousand crack troops and one general to deal with.

I beg to differ. I have heard this from the local elders: “The Li people’s settlements are behind layers of mountains and forests, with treacherous footpaths that wind up and down the slopes. Cavalry cannot charge up such heights, and their strong men often lie in ambush along the paths to obstruct travelers. When we arrange our formations to await them or beat our drums to attack them, they are not our match, but they always flee helter skelter into the mountains and forests and wait for us to leave. Against just one of their men, flaunting his defiance like a sparrowhawk spreading its wings, even our best warriors would not be able to display their bravery, and even the imperial guards would not be able to achieve victory, let alone one general looking down his nose at him?”

Some others have argued: “Sending in reinforcements after failing to defeat them is not a good strategy either. If the bandits hear that we have launched a massive offensive, they will surely come out in full force. Like cornered animals, they will fight to the death even against ten thousand crack troops. If we send armored troops into unfamiliar territory, pitting their weaknesses against the enemy’s strengths, we can only prevail with at least thirty thousand men. Moreover, we cannot conquer them with just one campaign, and should plan to achieve victory within three years.” But in these coastal lands with salty, infertile soil, how could the people bear having to support thirty thousand troops with three years’ worth of grain? Moreover, if we conquer the land [of the Li], we will surely have to turn it into prefectures and counties. But how can Hua people live comfortably deep in the mountains and valleys, where jackals, wolves, and demonic spirits (wangliang) dwell, and the water and soil are plagued by disease? If they cannot, then we will gain the land only to lose it again.

Some others have argued: “The Li people only disrespect the frontier clerks and insult our commoners because the law does not punish them for it. At present, those who commit murder only have to pay a fine in cattle and sheep. How is that enough to hurt them? If we encamp armies in their lands and offer them a chance to reform their ways, changing their clothing to [our] robes and caps, and letting them submit as imperial subjects, with the same laws and corvée and tax obligations as our commoners, then they will be easy to govern.” Those in authority believe this to be true. Why? Because they think the Li fear death and will surely obey us, such that without bloodshed, we can gain an area a thousand li across in size and never again have to worry about warfare and the cost of military deployments.

I beg to differ. The nature of barbarians (Yi-Di) is like that of dogs and pigs. One can change their clothing, but not their natures. If they, fearing death, accept our orders and agree to become our subjects, we do not know if they will again pose a threat in future. Can we guarantee that the laws will never be overly harsh, the taxes will never be levied at inappropriate times, and the officials and clerks will never be corrupt? I have heard this from the local elders: “In the past, when corvée obligations were replaced with cash taxes, we commoners all wanted to abandon our caps and robes and adopt mallet-shaped topknots, leave our ancestral graves behind and flee into the mountains and forests [to join the Li].2 Why else would we do this, if not to pursue happier lives?” Would it not be hard to make the Li people give up their way of life to adopt one with greater burdens? That is like rearing tigers and wolves in pit traps, or keeping a venomous snake as a pet on one’s dinner table. It would be wrong to claim that it is tame and will not bite.

Some others have argued: “The Li people live in barren lands and rely on Hua people for salt, wine, grain, silk, and tools like axes and farming implements. They trade for these with sandalwood and kapok fiber. Why should we continue to supply these bandits with weapons and grain? We should order the frontier officials to impose strict controls on the movement of merchants, and [the Li] would then be impoverished.” Those in authority will surely believe this to be true. Why? Because they think we can in fact impoverish the Li without impoverishing ourselves.

I beg to differ. In these coastal prefectures and counties, we can only have settlements of commoners and officials, and support troops and accumulate resources, by relying on merchants. The merchants who would brave the dangers of wind and waves and cross ten thousand li of inaccessible terrain, gathering here year after year, are the ones whose greed for profit is truly exceptional. As soon as we cut off the trade that the Li people enjoy, the merchants would stop coming, and we would ourselves be impoverished in three ways. First, we would no longer be able to meet our annual quota of commercial taxes; second, we would no longer be able to pay our soldiers and officials their salaries; third, we would be short on clothing and food and would then suffer from hunger and cold. The Li people, on the other hand, can always survive by chewing on grass and herbs and eating wild game raw. How then would we be able to impoverish them?

A physician treats an illness by treating the parts of the body that are already diseased, not the parts that are still well. If a boil grows on the head, then one treats the head; if it grows on the foot, then one treats the foot. One never does acupuncture on the back for a head ailment, or on the chest for a foot ailment. Now the Li people are just petty frontier bandits, but those making the arguments would stir up bitter conflict over petty disputes, forgetting that a single spark can set a whole plain on fire. Is this not treating a part of the body that is still well? The local elders say: “The Li people are large in number, but they cannot raid us [in full force].” Why? Because they don’t have rulers and chiefs to lead them, nor do they have unified laws and commands. Now, they can only encounter the frontier officials if they gather a raiding party of one hundred men with ten days’ worth of food. How can it be easy for them to gather ten days’ worth of food? The richest among them can only slaughter one cow to feed his warriors in a feast; once they are fed, they are ready to fight, but they leave at dawn and return by dusk. If we remove all crops from our fields when they come and raid, causing them to leave empty-handed and have nothing to make up for their expenses, why would they continue going to all that effort only to earn our enmity?3 The only danger would be that of them taking hostages.

However, if we investigate the root of the problem [of hostages], the fault lies with us and not them. The local elders say, “The Li people are by nature honest and simple. They do not have written documents and contracts and only use notches on wood and knotted ropes to keep records. Because of this, the Hua people take advantage of their stupidity and steal their possessions, but they do not dare to complain to the officials. Why? The officials do not understand their language, while the clerks demand bribes from them. They are aggrieved and have no means to seek redress, and can only take hostages to demand compensation.4 If the officials were capable of addressing their grievances, and the law was capable of preventing them from being taken advantage of, they would be like little children who love their parents. What fear would there be of them making a complaint and then taking a hostage?”

If I were one of those in authority, my best strategy would be to improve my own governance by ordering the officials to enforce regulations strictly. If anyone buys goods from the Li people but does not pay them, the state will pay them double every year as compensation, and the offender will be executed and his family enslaved. If a clerk dares to ask for bribes and is not disciplined according to the usual regulations, and if the prefect or magistrate does not report him, the governor will arrest them and await instructions from the imperial court. In addition, rewards will be instituted for able officials. In this way, then the able will be motivated to do their best, while the lazy will be punished. The greedy clerks and cunning merchants will not dare to indulge in criminality, and the frontier will naturally become peaceful.

The local elders also say: “In the past, one could travel across Zhuya (Hainan) by both the eastern and western roads without any danger. But now, an entire area seven to eight hundred li across has been overrun by bandits. The officials’ communications and the traveling merchants all have to go by sea routes. This problem has to be fixed.” I believe that if we achieve victory [over the bandits] through military force, the roads will be blocked again as soon as we withdraw the troops. If, however, we use profit to satiate them, the bandits’ greed will prevent them from rebelling again. If the imperial court contributes several officials as envoys to them, this would be worthier than using an army. Now, when the Li people seize the livestock of frontier commoners, the largest and wealthiest families among them have no more than ten or more slaves. If the officials go directly to these families, enumerate their crimes, and confiscate their slaves, they will not dare to resist due to sincere amazement at these men.5

I believe that this task can also be performed by the officials: Bringing gifts of gold and silk, go and speak to the Li, explaining the costs and benefits and intimidating them with threats of disaster and promises of prosperity. If the Li can reopen the old roads and allow travelers to use them without obstruction, then the officials would register those who submit reverently and request that the imperial court appoint them to an office with an annual salary. Such offices would only be responsible for ten or more men and receive a thousand strings of cash a year. Now, in Zhuya we have a garrison of one thousand troops deployed, costing no less than ten thousand strings of cash each year. If we used just ten percent of that as salaries for the Li people, we could eliminate the need for a thousand-man garrison.6

- That is, a minor irritant. ↩︎

- This is a reference to the labor recruitment law, one of Wang Anshi’s reforms, which sought to raise revenue by changing the traditional corvée obligation into a cash tax. ↩︎

- It is unclear whether the author is recommending a scorched earth policy of setting fire to fields when raiders arrive, or a more moderate policy of removing the crops beforehand, which might not be practical without not enough advanced warning. ↩︎

- Fan Chengda’s (1126-1193) Guihai yuheng zhi (Gazetteer for Governors of the Southern Frontier) of 1175 includes an account of how such hostage situations arose. The text was heavily abridged in the Yuan and early Ming periods, but Ma Duanlin’s (1254–1323) Wenxian tongkao (Comprehensive Investigation of Texts), completed in 1307, preserves long quotes from the original version that relate to the southern frontier peoples, including this one:

“[The Li] are extremely trustworthy when trading with merchants from the prefectures, but they cannot stand being swindled. If a merchant is trustworthy, then they treat him like family and lend him goods generously. They look forward to him visiting them once a year, and if he does not visit, then they keep thinking of him. If he breaks his agreement and does not come, then for defaulted loans above one coin, even after decades have passed, they will capture a man from his prefecture and hold him hostage, putting his neck in a cangue and caging him behind wooden bars. They release him only if the debtor comes and compensates them. If the debtor has already moved far away, or died, then an innocent man remains in captivity for years until he dies. They then wait for another man from the debtor’s prefecture to come and again place him in a cangue and keep him as a prisoner. The situation is only resolved if the hostage’s family goes to the debtor’s family and berate him angrily, demanding that they pay compensation, or if the hostage’s fellow townsmen raise funds to pay.” ↩︎ - The author seems to be suggesting, rather naively, that the Li will be cowed by the awesome moral authority of higher-ranking officials from the imperial capital and will not fight back to avoid losing their slaves. ↩︎

- The math here seems faulty, as it assumes that only one Li official would need to be appointed to ensure order among the many different Li groups. In reality, there would have to be at least ten, thus making this policy no less costly than the garrison. ↩︎