For information on Su Shi, see source 3.4.

Su Shi composed this inscription shortly after returning to the mainland of Guangdong after three years of political exile on Hainan island (in 1097–1100). It was written for a local shrine to a Han dynasty general who had borne the official title “Wave-quelling General.” Su notes that both Lu Bode of the Western Han and Ma Yuan of the Eastern Han had been given this title, and either of them could be honored at the shrine, since both had been pivotal in the establishment and maintenance of Han rule in the Lingnan region. He acknowledges that the history of Chinese rule in Hainan has not been uninterrupted. But he then argues that due to centuries of civilizing influence brought in by Chinese refugees, it is no longer a barbaric place and should be considered an integral part of the Central Lands core.

~~~~~

There were two Wave-quelling Generals in the Han dynasty, and both accomplished much good for the people of Lingnan. The first of these was Lu [Bode], the Marquis of Pili. The second was Ma [Yuan], the Marquis of Xinxi. Rulers since the three dynasties (Xia, Shang, and Zhou) had been unable to rule over the Southern Yue. The Qin briefly penetrated the region and appointed officials there, but it soon reverted to barbarism (Yi). This changed when the Noble of Pili attacked and conquered this country, after which [the Han] established nine commanderies in it.1 However, in the Eastern Han, two women named Zheng Ce (Trưng Trắc) and Zheng Er (Trưng Nhị) rebelled in Lingnan and took more than sixty cities.2 Emperor Shizu (Guangwu, r. 25-57 CE) had only just pacified the subcelestial realm at this time, and the people were tired of war. He had already sealed off the Yumen Pass and declined to [reestablish the former protectorate] in the Western Regions. How much less worthy of the imperial army’s attention were these southern wastelands? If the Marquis of Xinxi had not fought hard [to crush the revolt], then the nine commanderies [of Lingnan] would still be folding their robes to the left to this day.3 Judging from this, the two Wave-quelling Generals have equal claim to be worshiped at a shrine in Lingnan. It is impossible to determine which one it is based on historical records alone.

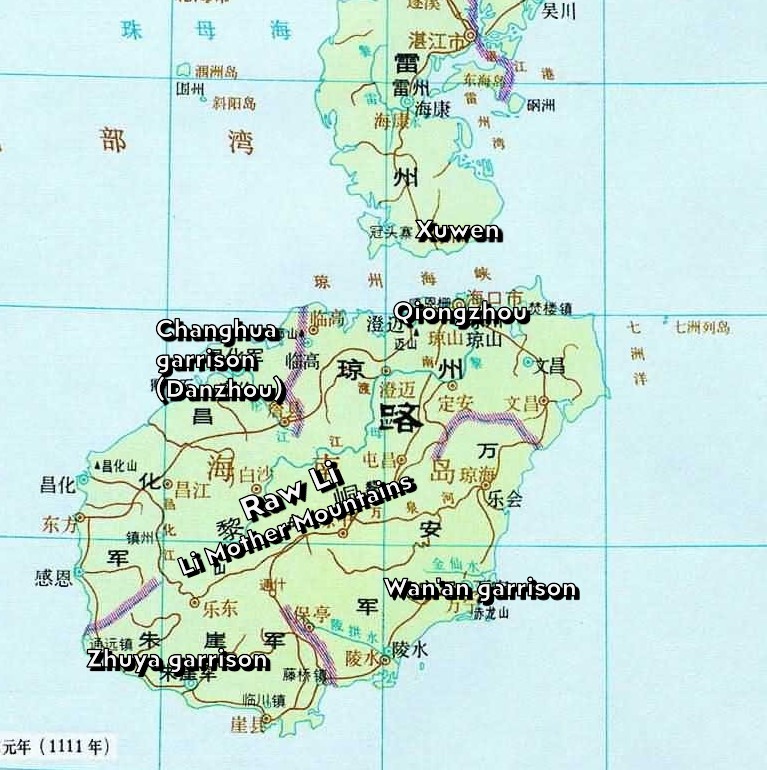

When one crosses the sea from Xuwen county to get to Zhuya (Hainan), one gazes south at the mountain ranges [on the island], shrouded in mist and barely visible.4 When boarding the ship and preparing to set sail, one is light-headed and trembling, frightened out of one’s wits. On the coast [at Xuwen county] there is a Shrine to the Wave-quelling General, and in the Yuanfeng era (1078–1085) an imperial edict was issued conferring the title King of Manifest Loyalty on the general. Everyone who crosses the sea first goes and seeks a divination there, asking, “Can I cross safely on such-and-such a day?” Only if the answer is auspicious does he dare to cross. People trust [the shrine] like they do a measuring stone, believing that it will never deceive them.5 Alas, how could this be possible unless the general’s moral charisma was truly great?

Since the Han dynasty, we have alternated between establishing and abolishing the commanderies of Zhuya and Dan’er.6 Yang Xiong said, “The abandonment of Zhuya commandery was Jia Juanzhi’s great contribution; if not for him, we would have exchanged the lives of clothed men for those of shelled and scaled creatures.”7 These words were appropriate at that time, but from the end of the [Eastern] Han to the Five Dynasties (907-960 CE), many refugees from the Central Plains have made their homes here. Now it has become a civilized and refined place, with robes and caps and rites and music. How could we still speak of abandoning it? The people of four prefectures view Xuwen like a throat8; those who cross from north to south, and from south to north, rely on the Wave-quelling General like a compass. How could they dare not to be reverent to this deity?

I, Su Shi, was exiled to Dan’er for three years due to an offense.9 Now, I have been permitted to relocate to the mainland (“north of the sea”), and my journeys both to and from [Hainan] met with favorable winds. Feeling that I have nothing with which to repay this blessing from the gods, I have composed this stele inscription and a poem to go with it.

[Translator’s note: I have not translated the poem, which is not one of Su Shi’s better works.]

- In 111–110 BCE, Han naval forces commanded by Lu Bode conquered the Southern Yue kingdom in the Guangdong region, as well as the island of Hainan. ↩︎

- See source 5.2. ↩︎

- An allusion to Confucius’s praise for Guan Zhong in Analects 14.17 (see source 1.3). ↩︎

- Xuwen county was at the southern tip of the Leizhou peninsula and thus the closest point of embarkation to sail to Hainan. ↩︎

- These stone weights were used to define standard units of measurement, such as the picul. ↩︎

- Both commanderies were established on Hainan in 110 BCE, but Dan’er was merged into Zhuya in 82 BCE. ↩︎

- For Jia Juanzhi’s role in the abolishing of Zhuya in 46 BCE, and Yang Xiong’s positive assessment of it, see source 2.4 and source 2.5. ↩︎

- The throat metaphor conveys the idea that Xuwen was an essential point on the route to Hainan, but also the idea of it being a dangerous sea route that could “swallow up” travelers. ↩︎

- Su’s place of exile was Changhua garrison (Danzhou, Hainan), which corresponds to the old Dan’er commandery. ↩︎