During the Tang period, the far southern prefectures of the empire were a common place of exile for officials who had offended the emperor or fallen afoul of factional politics at the imperial court. Fang Qianli was one such official. Fang passed the civil service examinations in 827 and rose to the position of an Academician in the Imperial College, but due to an unspecified offense, he was first posted out to Luling (Ji’an, Jiangxi) and then served successively as prefect of Duanzhou (Zhaoqing, Guangdong) and Gaozhou (Gaozhou, Guangdong). Little is known of his life, but he is believed to have died after 840, possibly in Gaozhou. He wrote two short books during his southern exile, the Touhuang zalu (Miscellaneous Records of an Exile to the Frontier) and Nanfang yiwu zhi (Gazetteer of Exotic Things in the South), but both are lost. Numerous fragments of the Touhuang zalu have been preserved in the Taiping guangji and the Taiping yulan.

The fragments below provide valuable glimpses of the society, administration, and culture of Hainan island under Tang rule in the ninth century. Following its abandonment by the Han empire in 46 BCE (see source 2.4), Hainan did not become a site of Chinese colonization again until the sixth century, when the Liang dynasty established a prefecture on the island and delegated its administration to the indigenous Li 俚 leader Lady Xian and her family. The Sui and Tang empires established other prefectures on Hainan, but the island (which the Tang Chinese called Haizhong 海中, “in the middle of the sea”) seems to have remained a rather lawless place, with rampant corruption and pirates preying on merchant ships sailing to Guangzhou and Jiaozhou (Hanoi). The perilous nature of the sea routes near Hainan seems to have given rise to legends about the Hainan indigenous people’s ability to control the winds magically. It’s unclear whether Fang Qianli ever visited Hainan himself, but he was clearly fascinated by these legends.

~~~~~

The women of Haizhong (Hainan) are good at sorcery, and men from the north sometimes marry them. Even if they have disheveled hair and hunched backs, they can cause men to be infatuated with them and to remain faithful unto death. If a man should abandon one of them to return to the north, his ship ends up becalmed on the sea and unable to move further, and he then turns around and sails back to her.

Chen Wuzhen, a resident of Zhenzhou (Sanya, Hainan), had a fortune worth ten thousand gold coins and was a great local lord in Haizhong (Hainan). In his warehouses were hundreds of rhinoceros horns, elephant tusks, and turtle shells that he had previously acquired from merchants from the Western Regions (Central or West Asia) who were shipwrecked and drowned. The people of Haizhong are good at magic, which they customarily call de moufa 得牟法 (“seizing magic”). Whenever merchant ships pass along the sea routes, they steer well clear of the five commanderies (prefectures) of Haizhong, but if by ill fortune one is blown off course by winds and enters the boundaries of Zhenzhou, then the people of Zhenzhou climb to the top of a mountain and chant their magic spells with their hair untied. This raises the wind and waves and prevents the ship from leaving. It always drifts to the place where the spell is being cast and then stops. Wuzhen was able to become rich via such means. The Bandit Suppression Commissioner Wei Gonggan treated Wuzhen respectfully like his own elder brother. When the government confiscated Wuzhen’s wealth, Gonggan’s own home was left empty as well.1

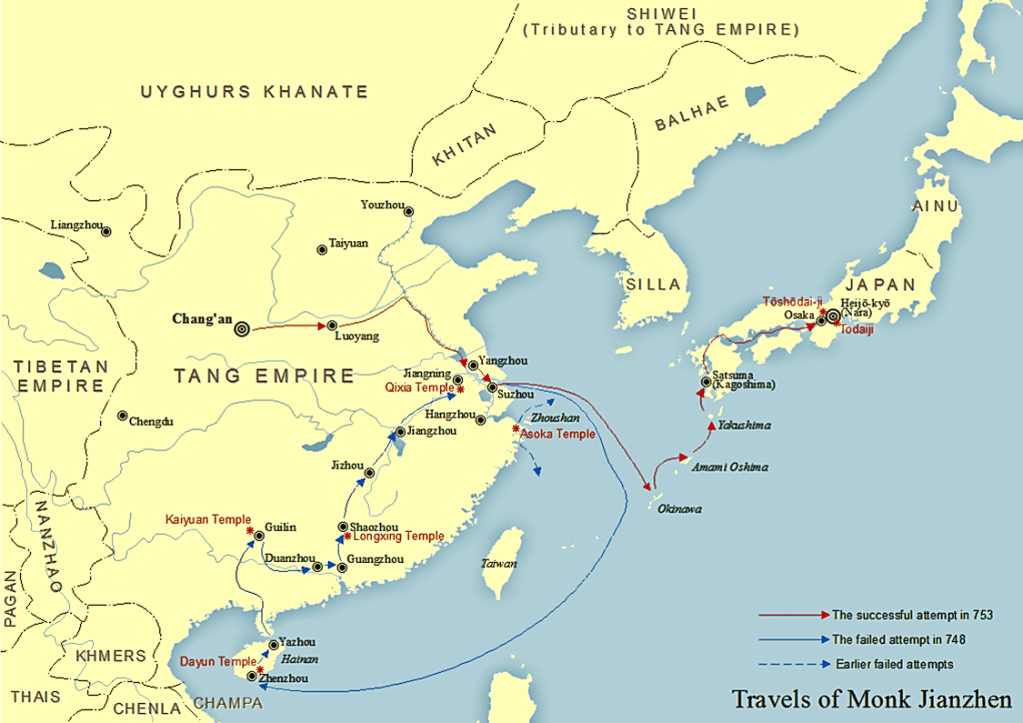

[Translator’s note: Although there are elements of fantasy in the story of Chen Wuzhen, his career seems to mirror that of a real Hainan pirate described in Japanese scholar Ōmi no Mifune’s (722-785) Tō Daiwajō Tōseiden 唐大和上東征伝, an account of the Tang monk Jianzhen’s (688-763) life and travels. In 748, during his fifth attempt at sailing to Japan, Jianzhen’s ship was blown off course to Zhenzhou on Hainan. There, he encountered an extremely wealthy local pirate named Feng Ruofang:

Feng Ruofang, a leading chief in the prefecture [of Wan’anzhou (Lingshui Li Autonomous County, Hainan)] invited Jianzhen to his home and hosted him for three days. Every year, Ruofang captured two or three Persian (Bosi 波斯) ships, seized the goods on board and kept them for himself, and enslaved the crew.2 He had so many slaves that to see all of his slaves’ homes, in one village after another, would take three days on foot from north to south and five days on foot from east to west. When Ruofang entertained his guests, he always lit frankincense as candles, using up more than a hundred catties of it at one go. In his backyard, sappanwood was piled up like mountains in the open. His wealth in other commodities was of the same degree.

Forty li southeast of Yazhou (Qiongshan, Haikou, Hainan) lies Qiongshan commandery.3 The prefect [of Qiongshan] commands five hundred soldiers. He also serves concurrently as Bandit Suppression Commissioner over five commanderies (prefectures), including Danzhou, Yazhou, Zhenzhou, and Wan’anzhou. All the taxes from these five commanderies are directed to the Bandit Suppression Commissioner’s office. Four commanderies are subordinate to Qiongshan, and Qiongshan itself is subordinate to Guangzhou. As for the yearly revenues of the five prefectures on Haizhong (Hainan), the Surveillance Commissioner is not allowed a single string of cash; all go to supply Qiongshan. The needs of the local garrison—both military funds and food—are provided from the commanderies north of the sea.4 Whenever a new governor is appointed to Guangzhou, the court grants him five hundred thousand strings of cash for banquets and largess.

Although Qiongshan is but an outpost in the sea, each year it receives quantities of gold and cash that even the Military Commissioners for the southern frontier cannot rival. Its prefect, Wei Gonggan, was greedy and cruel. He seized the sons of good families and made them his slaves, driving them like dogs and pigs. He had four hundred female slaves, most of them skilled artisans: some wove patterned silks and fine gauzes; some carved horns into vessels; some smelted and forged gold and silver; some crafted precious woods into implements. His household was like a marketplace, with daily inspections and monthly assessments, and the artisans lived in constant fear of failing their quotas.

Earlier, when Gonggan was prefect of Aizhou (Thanh Hóa, Vietnam), there had stood within its territory the bronze pillars erected by Ma Yuan.5 Gonggan ordered them melted down and sold the metal to Hu (West Asian or Central Asian) merchants. The local people did not know that these pillars had been cast by the Wave-quelling General (Ma Yuan), but believed them to be divine objects. They wept, saying: “If the prefect destroys these, we will all be killed by the sea god!” Gonggan paid them no heed, until the people went to the Protector-general [of Annan], Han Yue, and lodged a complaint. Han Yue sent him a letter of severe reproach, and only then did he desist.

When Gonggan later governed Qiong, he found many stands of rare trees called wuwen and qutuo. He drove woodworkers along the coast to cut them. Some who could not meet their quotas killed themselves with their own axes.

The year before last, when Han Yue’s son-in-law’s term in office ended and he was due to be replaced, Gonggan prepared two great ships: one fully laden with wuwen wood wares mixed with silver, the other with qutuo wood wares mixed with gold.6 He had sturdy soldiers escort them eastward across the sea to Guangzhou, but the hulls, though solidly built, were heavy with gold; within a few hundred li, both ships capsized, and untold wealth was lost.

The classics say: “Ill-gotten gains will be lost in unnatural ways.”7 Gonggan acted immorally, harming the people to enrich himself, exhausting the very marrow of the Yi and Lao to fatten his own house. He only defiled his name and gained not the least benefit. By covering up his evil deeds, he might have escaped human punishment, but the spirits would surely punish him.

- The implication seems to be that Wei Gonggan was corrupt and had received many bribes from Chen Wuzhen, which were now also confiscated. This impression is confirmed by another anecdote about Wei (see below). ↩︎

- Some scholars have argued that the Bosi here should be understood as a location in Southeast Asia, rather than Iran. This controversy hinges on disagreements over whether Iranian maritime merchants were active in the South China Sea in the eighth century, as well as a theory (originating with Edward Schafer) that Persian and Arab slaves of Feng Ruofang were the “Dashi and Bosi” who reportedly attacked and looted Guangzhou in 758. ↩︎

- Qiongshan commandery was also known as Qiongzhou prefecture. ↩︎

- That is, on the mainland. ↩︎

- According to a legend first attested in fourth-century sources, Ma Yuan erected bronze pillars to mark the southernmost point of Han territory after defeating the rebellion of the Trưng sisters in 43 CE (see source 5.2). Legends that later circulated in Đại Việt claimed that Ma Yuan made an oath when erecting the pillars, declaring that Jiaozhi would fall when the pillars were destroyed. ↩︎

- These were parting gifts for Han Yue’s son-in-law (a local official in Guangzhou), but were obviously meant to curry favor with Han Yue. ↩︎

- This is a quote from the Liji document “Daxue” (Higher Learning). ↩︎